Magnetism is one of the most fundamental forces of nature, yet it often feels like magic when a piece of metal leaps toward a magnet. To understand why magnets attract metal, we must delve into the microscopic world of atoms and the behavior of subatomic particles.

The Fundamentals of Magnetism

At its core, magnetism is a force of attraction or repulsion that acts at a distance. It is caused by the motion of electric charges. Every substance is made of atoms, and every atom has electrons circling a nucleus. These electrons carry an electric charge and spin, which creates a tiny magnetic field for each individual electron.

In most materials, these tiny magnetic fields point in random directions, effectively canceling each other out. However, in certain metals, these fields can align to create a net magnetic force. This alignment is what distinguishes a magnetic material from a non-magnetic one.

The Role of Electron Spin

The primary source of magnetism is the spin of electrons. Electrons possess an intrinsic property called spin, which makes them act like tiny bar magnets. In many elements, electrons are paired up in such a way that their spins are in opposite directions, neutralizing their magnetic effect.

In metals like iron, nickel, and cobalt, there are unpaired electrons. These unpaired electrons allow the atom to have a magnetic moment. When a group of these atoms aligns their magnetic moments in the same direction, they form what scientists call a magnetic domain.

Ferromagnetic Materials: The Magnetic Elite

Not all metals are attracted to magnets. The ones that exhibit strong attraction are known as ferromagnetic materials. This category includes common metals that we interact with daily.

- Iron: The most well-known magnetic metal, used in everything from construction to kitchen appliances.

- Nickel: Often used in plating and stainless steel alloys.

- Cobalt: A critical component in high-strength magnets and batteries.

- Gadolinium: A rare earth metal that shows magnetic properties at low temperatures.

How Magnetic Domains Work

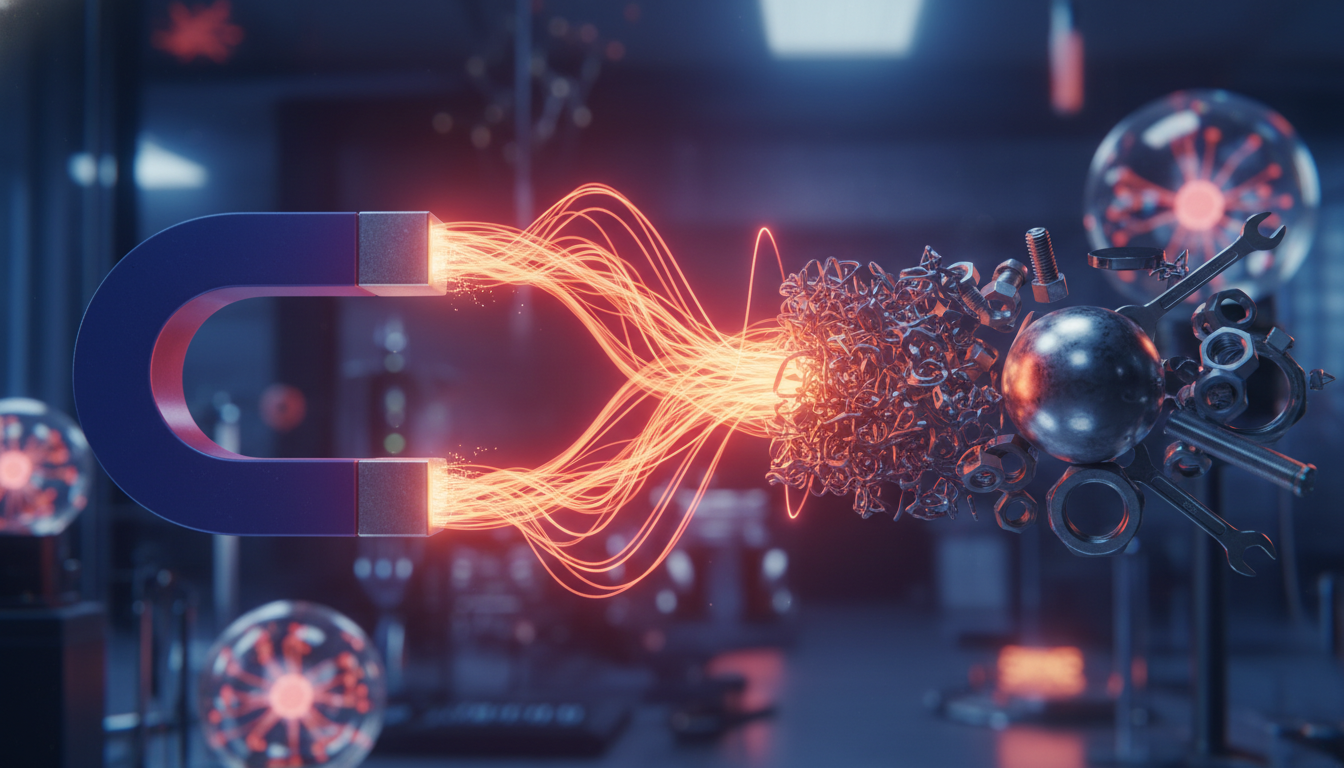

In an unmagnetized piece of iron, the magnetic domains are pointing in various directions. When a permanent magnet is brought close to the iron, the external magnetic field exerts a force on these domains, causing them to rotate and align with the field. This temporary alignment turns the iron itself into a magnet, resulting in an attractive force.

Why Some Metals Are Not Attracted

It is a common misconception that all metals are magnetic. In reality, metals like aluminum, copper, and gold do not show noticeable attraction to magnets under normal conditions. This is because their atomic structures do not allow for the formation of stable magnetic domains.

Metals like copper are diamagnetic, meaning they actually create a very weak, opposing magnetic field when exposed to a magnet, though this effect is usually too small to notice. Aluminum is paramagnetic, meaning it is very weakly attracted to magnets, but the force is so slight that it cannot overcome gravity or friction in everyday scenarios.

The Influence of Magnetic Fields

A magnetic field is the invisible area of influence surrounding a magnet where the magnetic force is exerted. The strength of the attraction depends on the intensity of this field and the distance between the magnet and the metal object. As the distance increases, the force of attraction drops off significantly following the inverse-square law.

Temporary vs. Permanent Magnets

Some metals, like soft iron, are temporary magnets. They become magnetic only when inside a magnetic field and lose their magnetism once the field is removed. Permanent magnets, like those made from neodymium or alnico, retain their domain alignment for long periods, providing a constant magnetic field.

Practical Applications of Magnetic Attraction

Understanding why magnets attract metal has led to revolutionary technologies. From the simple magnetic strips on refrigerators to the complex components of MRI machines, magnetism is integral to modern life.

Industrial magnetic separators use these principles to remove metallic contaminants from food and chemical processing lines. In the tech world, hard drives use tiny magnetic regions to store vast amounts of digital data, proving that the science of ‘why’ has led to the ‘how’ of our digital age.

Conclusion

Magnets attract metal because of the alignment of electron spins and the formation of magnetic domains within ferromagnetic substances. While the process happens at a level invisible to the naked eye, the results are powerful and essential to both nature and human innovation.